"I still think of this as Logan Street," Jim Johnson said as we drove along Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. It was Memorial Day and we were going to see the parade downtown.

"It's been several decade since the street name was changed to honor Dr. King," I replied. "I'm sure Mr. Logan would be pleased that you still think of him."

"Logan was a man?" Johnson exclaimed. "I thought it was the name of a tree, like Pine, Sycamore, Walnut and the other north-south roads near here."

"Nope," I said. "I looked it up once. John Alexander Logan was a Civil War General from Kentucky who commanded the Army of Tennessee in Georgia and then became a senator from Illinois. I'm not sure what his name is doing in Michigan."

"Is that so? I guess the street wasn't much of a memorial to him if people don't know who he was," Johnson said.

"Ironic, too. I read that he was also the founder of Memorial Day."

As we drove along, Johnson read aloud the names of the cross streets. "Bailey… Everett… Barnes." Then he shook his head. "Who knows who any of these people are? Or were! Trivia. That's all it is."

I agreed. "Logan could just as well have been named after the guy who developed the loganberry, the late 19th century horticulturist and Supreme Court justice, James Harvey Logan."

Johnson was not listening to me. He pondered, then said, "You know, they should have renamed the street Douglas instead."

"Douglas?" I exclaimed. "Talk about trivia. Who the hell is Douglas?"

"It's a fir," he answered. "It follows the tree names scheme."

– Ω –

[ Go to end ]

If you think about it, naming a street after a human being is a curious practice – almost pointless. For one, hardly ever does the honoree have a connection to the street or anything on it. For another, rarely does anyone seeing the street label pause and reflect on the memorialized soul. Almost certainly for residents and visitors those syllables that once pointed at the individual will only paint a mental picture of that place. And it may not be a pretty picture.

I remember driving down Beaubien Street in downtown Detroit decades ago. I gawked at the old and uneven three-stories dressed in tattered siding and peeling paint and trimmed with narrow dirt lawns and vagrant artifacts. I grimaced at the sight of the poor inhabitants who walked, talked, laughed, lazed, and played, not knowing the predicament I saw them in, trapped there on wretched Beaubien Street. If that French settler who farmed a ribbon of land here two centuries earlier could have peered into the future and seen the poverty and blight, Antoine Beaubien might have titled his property under another name, being content to hide his surname in the shadows of history.

A more renowned example is the street duo of Haight-Ashbury that evinces an inelegant picture of the 1960s hippie movement. Henry Haight, a prominent local banker in San Francisco who founded the Protestant Orphan Asylum, would surely revile at the association. (Ashbury comes from a district in England located midway between Ashfield and Canterbury.)

Countless examples can be given. With good intentions, people's names get stuck on buildings and roads with much pride and honor, in hope and memory. But intentions are momentary, pride and honor evaporate, and hope and memory fade. The black hole of time sucks the meaning out of the memorial, and the origin of a name gravitates to trivia, then obscurity. It seems a natural law of our culture.

That may not happen as quickly with Dr. King's boulevard. (Perhaps the late Mr. Logan might not have lost his street had it been called General John A. Logan Blvd.) Even though the syllables "Martin Luther King, Jr." are becoming ever diluted as the name gets tagged onto hundreds of streets, schools, parks and libraries, its meaning as the man who "had a dream" will not be soon forgotten. On the other hand, rarely does a thoroughfare have to bear such a train of syllables. Not even George (or was it Martha) Washington got it all on his (her) avenues in so many American cities.

Can you imagine living on Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. and having to scribble this epitaph (to the 16th century priest) within an epitaph (to papa King) within an epitaph (to the assassinated civil rights leader) every time you wrote your address? This triple commemoration begs to be shortened to M. L. King, or MLK. One could easily imagine it being jokingly called Milk Blvd. Perhaps it will end up being called simply King Blvd., whereupon feminists in the future will demand a Queen Avenue. Someone suggested to me that they should have renamed the former Logan Street after both the civil rights leader and former Chief Justice Warren Burger, thus yielding the compromise street name of Burger/King Blvd.

The odd thing about the City of Lansing renaming Logan Street to MLK Blvd. (See what I mean?) is that it had as much direct connection to Dr. King as to General Logan – none. The renaming was simply an affirmative action for street names. Yet there was a famous black leader who does have links to the city, Malcolm X. He was born Malcolm Little and went to school in Lansing, Michigan during the 1930s. Although he has his detractors, many consider him an important legacy in the Black movement.

The problem was just what exactly to name the memorial street. Certainly not Little Street – referring to that "slave name" he was born with. Using his Harlem name, Malcolm X, might be appropriate since he liked Malcolm, and the X refers to his unknown heritage lost with the enslavement of his ancestors. But then again he might have preferred the Muslim name he took a year before his assassination. "Could you deliver a pizza to 1173 South El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Boulevard?" In the end, in 2011, a three-mile-long stretch of Main Street became Malcolm X Street.

I don't know if his final name had anything to do with it, but you will not find many streets memorializing him. Only in the cities of Brooklyn, Dalls, Lansing Sacramento will you find a street named after him.

In any case, I doubt there will be any more memorializing with street names in Lansing for a long while. After King got his boulevard, the residents of Mexican ancestry persuaded the city council to change the name of Grand Avenue, a mile-long downtown street, to César Chávez Avenue. An outcry resulted, not from any disrespect for Mr. Chávez but because the populace had had enough name changing. A petition put the question on the ballot and a majority of voters returned the old "Grand" name to its street. San Franciscans likewise fought to return César Chávez Street back to its original name, Army Street, but failed.

The same story of community fighting over street names is told across the country. But the wrangling is not always over a memorial name. In 1998, in Concord, New Hampshire, there happened to be two Walnut Streets and city authorities were concerned about emergency vehicles not responding to the correct address. So the six families of the newer street were asked to come up with another name for their road. The neighbors decided to make a party out of their meeting, but after the initial amusement wore off they found that agreement was not easy. Suggestions like Memory Lane, Woodpecker Street, Lois Lane, and, yes, even Martin Luther King Way were made. But all were rejected. After some squabbling, only one name got a majority vote, Black Dog Lane, because so many black dogs roamed the neighborhood.

But a minority resisted and urged the city council to reject that name. One woman objected because her son had been bitten by a black dog. Soon some of the residents of old Walnut Street were not talking to their neighbors. What had started out as fun had turned into fury. A few weeks later, a new meeting was held, this one in serious and somber mood. The "Black Dog" faction relented and in the end the group unanimously voted to live on Orion Path. I wonder if Harmony Lane was a candidate?

Usually streets get named not by residents but by those with money enough to stroke their own ego. When agricultural land is engrossed by a growing suburb, invariably a byway or two is labeled after the farmer who toiled there, or his wife, or his favorite heifer. Developers, too, often and immodestly placed their own names on streets in emerging subdivisions. And we must not forget our pork barreling legislators. In the 1970s, Michigan Senator Garland Lane was instrumental in providing funds for an upstart university north of Detroit and so a street was named Gar Lane. Clever, yes, but Gar Lane Lane would have been devilish.

Buildings, like streets, are magnets for personal names. The profusion of edifices in our growing culture is like a subway wall waiting for the graffiti of human labels. But naming public buildings can be a delicate matter. Naming the State Law Building after a Democratic governor is only possible if the executive office building is named for a Republican governor. School buildings once were tagged with a code like P. S. #87, or some logical designation like Northern High School, but now they get the patronymic of a dead school board member like Van Pickle Elementary School to the embarrassment of the students. The vast majority of schools in the United States have memorial names, the most common being Lincoln, Jefferson, Kennedy and recently King.

Naming a public school after a dead hero of history or late local lion is about as creative as using the community name, such as Oak Park Middle School or Eaton Rapids Elementary School. For a comparison, look at the imaginative names now being given to for-profit charter schools – names like North Star Academy, Neighborhood House, Landmark Schools and Explorations. A New Yorker cartoon shows a school building with a sign in front reading "THE KNOWLEDGE HUT" and in small print underneath "FORMERLY P. S. 102."

Buildings like streets can run into difficulties in the course of gaining a name. I worked in what was once the Stoddard Building, formerly owned by the bank across the street and named after its president Howard J. Stoddard. Bought and renovated by the Michigan Legislature, it became the Senate Office Building, or, to their chagrin, S.O.B. As you might expect, the next prominent person to die got his name on the building. Fortunately it wasn't a former senator named Tall.

At the Mt. Clemens Hospital in Michigan one of the benefactors of the institution was a physician named Charles Ward. By his contributions and leadership, a new wing was added and named after him, the Ward Annex – but I like to call it the Ward Ward.

Some surnames just don't suit buildings. Can you imagine naming a hospital after Al Gore? And Roach – even though it is not an uncommon name, I doubt there will ever be a hotel memorializing it. On the other hand, a hospital named after Nathan Hale would be all right. Not so for Dr. Jack Kevorkian – if they want to honor him it should be with a dead end street.

Advertisement

The naming and renaming of streets, buildings, towns, parks and whatnot after people has been going on for ages. But streets are special kinds of places. They are moving and static at the same time; you can travel along River Blvd. and live on Pond Avenue. Streets are part of addresses as well as directions to those addresses. They belong to residents and visitors alike. And they usually come in bunches, getting named either systematically like battleships or capriciously like the seven dwarves.

Of all the things that get named, streets seem to get the most diverse labeling. Nothing in the language is disqualified from being used. We find streets being named after not only people, but also cities, states, Indian tribes, trees, flowers, and all kinds of fluff stuff like Skyline, Crestview, and Pleasant This and Pleasant That. Street names can be numbers or letters, utterly prosaic like North Street, almost poetic like Just-A-Mere Ave, or an ordinary dictionary word like Stadium, Duty or Electric.

Byways are such an integral part of our lives their names pop up in all sorts of unlikely places. Madison Avenue is not only a road in New York City but an icon of the advertising world. Even though Lover's Lane is the name of several roads in the United States, it is often the nickname applied to secluded parkways where couples stop to discuss foreign affairs and such.

| Words to Designate a Street | |

| avenue | boulevard |

| circle | drive |

| court | driveway |

| estate | fair |

| gate | hollow |

| isle | jetty |

| knoll | lane |

| mill | narrow |

| orchard | park |

| quay | ridge |

| square | trail |

| union | view |

| way | woods |

|

(see Wikipedia entry for a complete list.) | |

Street signs sometimes reach beyond their roads and have an impact that is not only geographical but cultural as well. The table, Famous Streets, Roads and Byways, gives several examples of how a street name can take on a new meaning.

Like people names, streets have a kind of surname, or generic classification, as well as a first name. The first name is the important part, like 5th, Glendale, or Vine. The second, or generic, part alone will not help you find an address – words like Circle, Place, Avenue, etc. – but they do add distinction and perhaps a little color. There are dozens of these generic designations for streets, "street" being the most common. It originates from the Anglo Saxon mutilation of the Latin "via strata," or "layered (paved) way" and was used to refer to the superior Roman roads.

Other synonyms entered the language because "street" had become redundant. In large urban areas with numerous thoroughfares (A confused version of the term "through fare"), more variation was needed. So, for example, in the 19th century, when the city of Washington was being laid out, the French "avenue" (Avenir) was adopted. This brought a new sophistication to naming streets and other cities followed the lead, notably New York which gave the north-south roads the designation "avenue." By the end of the century, the word "street" was hardly ever used as part of a street name. But the popularity of "avenue" was not immune to creeping cultural change. In the 1920s, it was being replaced by "drive" in the subdivisions of the growing cities.

After World War II, community developers had discovered that houses sold more quickly if they were located on ways, crosses, lanes, places, and other creative fluff. And the generic designation did not even have to imply a byway of any kind, just a place, as with words like dale, forest, garden, and valley. Now it is possible to choose a byway's generic designation beginning with nearly any letter in the alphabet as shown in the table to the right.

The biggest impact on American and Canadian cities came with the founding of the Quaker colony by William Penn in 1682. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he found that the few streets there were called after the most prominent person living on them. Like the good Quaker he was, Penn disliked the aggrandizement of any one person over any other. So he insisted that no personal names were to be used in naming the streets. Penn devised a rational system of parallel roads that would be given rational designations. The north-south streets would be given numbers starting with 1st Street near the bank of the Delaware River. 1st Street eventually became Front Street. The east-west roads would be named after trees, like Chestnut, Locust, Spruce, and Filbert. Over time, however, the pull of chaos was too strong and eventually roads were named or renamed helter skelter after people, far-away places, and whatnots, resulting in a Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Christian Street, Passyunk Avenue, Wylie Street, Race Street, etc.

But Penn did start a trend – so many towns followed his example that a compilation of the most popular street names in the United States finds numbers and trees leading the list (see table Top 20 Street Names in the United States below.) Curiously, First Street is not among the top five on the list because in many towns, as in Philadelphia, it was named something else, like Front, River, Atwater, Edge, Market or whatever distinguished that primary road. One of the most popular alternatives to First was Main, but not enough so as to place it in the top five. Still with the help of Sinclair Lewis the phrase "Main Street" has become a coin of the language, a symbol of provincial small towns. In Vermontville, Michigan, the streets of East Main, West Main, South Main and North Main all meet at a point in the town that is mainly not so main.

| Top 20 Street Names in the USA | |

1. Second |

11. Pine |

2. Third |

12. Maple |

3. First |

13. Cedar |

4. Fourth |

14. Eighth |

5. Park |

15. Elm |

6. Fifth |

16. View |

7. Main |

17. Washington |

8. Sixth |

18. Ninth |

9. Oak |

19. Lake |

10. Seventh |

20. Hill |

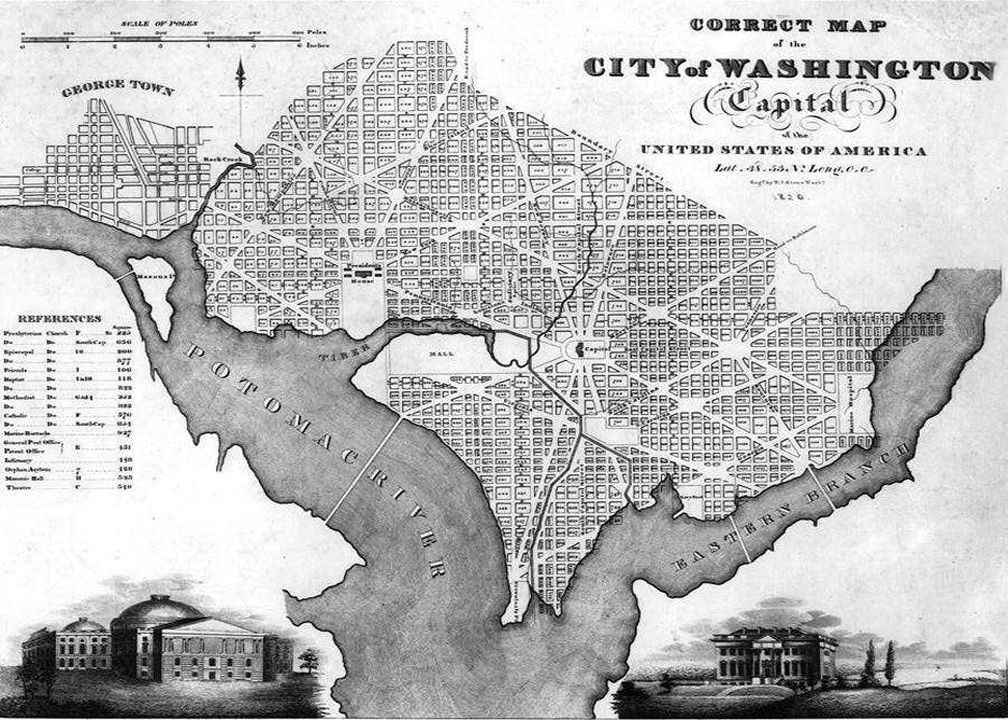

Among the towns following Penn's rational urban design was the United States Capitol in the District of Columbia. The municipality was created by Congress to be the seat of government in 1790 and was to be located on a site chosen by George Washington. He selected a place as close to his Mount Vernon as possible, a swampy 10 square miles straddling the Potomac River including 1200 acres of his own.

A Frenchman in the American Army Corps of Engineers, Pierre Charles L'Enfant, was given the task of planning the city byways. Using Versailles as a model he laid out streets in a grid pattern, adorning the intersections with circles and squares. To break the tiresome symmetry, he proposed grand avenues cutting diagonally across the grid to connect major buildings. L'Enfante might have had more to do with the scheme, but his ill temperament eventually caused George Washington to ask Andrew Ellicott to complete the project. But it was the commissioners of the new city who chose the scheme of assigning numbers and letters to street names. As for L'Enfante's majestic avenues, they would be named for the States.

The city grew in fits and starts and the rational approach to street names gave way to all kinds of aberrations. New lands added to the city brought a potpourri of street names honoring land owners and their family members. Duplicate names appeared on opposite sides of the city. Some byways changed names each block or so. After the Civil War it was not just the street names that were a mess. The roads were rutted and muddy, the parks overgrown, housing inadequate and expensive, and even the morals of the society were questioned. "Washington is not a nice place to live," wrote Horace Greeley in July of 1865.

Revitalization came in 1871, and by the end of the century improvements brought respect. In 1899, Congress enacted strict guidelines for the naming of streets in the District. Among the rules were the following:

This scheme produces a mirrored duplication of street labels emanating from the Capitol, so that there would be two 2nd Streets and two A Streets, etc. This required the addition of compass codes such as SW, or NE.

The changeover to the new system caused great headaches for the residents because so many streets had to be renamed to abide by the rules. 3rd Street became 4th Street, Columbus became 20th, Cincinnati became Cleveland, S became Cambridge, V became S, and on and on. By 1906, the task was completed and hardly any of the old names survived. Well, it was almost completed. The designation Indiana Avenue disappeared in 1907 because of construction, then reappeared as the name of a street that was called Louisiana Avenue because that name was given to a new street north of the Capitol.

Of course what good are rules without exceptions. For example, there is no J Street (probably because the letter could too easily be taken to be an I) but there is a Jay Street named after Chief Justice John Jay. Nor are there any X, Y or Z Streets. Half Street had to be inserted south of the Capitol. The diagonal South Dakota Avenue turns into 3rd Street, while the eely Michigan Avenue is hardly a diagonal at all. California and Ohio are "streets" instead of "avenues" like all the other roads named after States.

There are other exceptions to the rules, but you get the point. And it will only get worse. Each year city planners are confronted with a gale of new names proposed for current streets and new ones being built. Now you know why the tax code is what it is.

Sometimes a new era cultivates a new naming scheme. In the 1850s when States were sprouting across the continent, Penn's notion of designating roads by tree variety took root and a virtual forest of Oak, Elm, Pine and Maple Streets arose around the country. After the Civil War many cities grew outward and new roads memorialized land owners, war heroes and politicians. In downtown Chicago, for example, the numbered east-west street designations were replaced with presidents' names.

In the next century, planned communities looked for style by labeling their byways according to motifs and themes, and later less cultured developers settled for pastoral fluff like "Glen this" and "Green that."

In Detroit, the various naming schemes scattered about reveal the spasmodic growth of the city. Colonial names define the oldest parts of town, then numbered streets the next oldest. A dozen or so state names appear beyond these. A series of "lawns" such as Cherrylawn, Greenlawn and Roselawn radiate from center town to the northwest. We find a tribe of Indian names like Seminole, Seneca, and Iroquois in the south east. But on top of all the schemes, the predominant motif is patronymic chaos, from Washington to Sobrieski, Jefferson to Hafeli, Wanda to Gallagher.

In 1835, the people of Detroit wanted to honor their first mayor by naming a couple of streets after him. Thus there is a street named John R and another named Williams. A major thoroughfare honors a veteran of the War of 1812, General Charles Gratiot. For some obscure reason, the locals pronounce the avenue "grass shit" as opposed to rhyming it with patriot.

In the Houston area, isolated groups of numbered streets mark the city's past like carcasses in a desert. The rest of the road names are as diverse as the structures that cast shadows on the roads, everything from Marble to Wood, Big Stone to Tiny Tree. One can meander this booming metropolis and find street names like Laurel and Hardy, Bombay and Paris, Winter Bay and Summer Dew. There is even a Cocoa Street and a Cola Street. I wonder if they will ever name a road after that great 16th century German Augustinian priest, Martin Luther?

In contrast, Phoenix in Arizona has a marvelously consistent numbering scheme for its north/south roads. Every byway west of Central Avenue is numbered sequentially (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) and always called an Avenue – or sometimes Drive or Lane or Parkway. Every byway to the east is numbered sequentially and always called a Street – or Place or Road or Court or Way. As a result, there is a 5th Street and a 5th Avenue instead of a 5th St. N.E. and 5th St. S.E. as in Washington, D. C. The important thing, though, is that there are no exceptions to this scheme – number names for every single longitudinal road…except Mitchell Street, and Dayton Street, and Evergreen Street and a few others. Now, the east/west roads have their own scheme – they are named in a perfectly random fashion. So, if you are driving north on 7th Street, and you cross Oak Street, you can be one hundred percent sure that Pine or Elm or Cedar will not be the name of the next road.

Helena, Montana probably represents the typical small city in America. It has numbered streets also, but they are a meager lot, lost in the montage of themes, personal names, and random labels. Under the big sky you will find streets named after favored presidents like Grant and Cleveland, several tree types like Pine and Cedar, some female first names like Elaine and Lola, a few states like Kentucky and Alaska, dozens of surnames like Townsend and Ewing, and the miscellany like Euclid, Big Sky, and Fleet. In addition, you will find a Main Street, a stretch of which has the name Last Chance Gulch Street. Now there is a good candidate to be renamed Cesar Chavez Ave.

Everywhere in the U. S., it is clear that numbering streets is not an enduring scheme. Yet isn't it ironic that, in a society where so many people dislike number designations, so many communities adopted the numeric scheme for their byways in the first place. Apparently those early urban planners, hoping to tame nature with rationally named roads, did not understand that the citizens care more about sentiment than logic. Perhaps the efforts of the earlier planners would have been more appreciated had they used irrational numbers, like the Square Root of Two Blvd or Pi R Squared Parkway.

Advertisement

It is not just numbering schemes that are thwarted by progress. Any naming motif for a growing metropolis will fail over time – and for many reasons. Grid plans are particularly vulnerable. Inevitably, as the town's boundaries move out, a bend in a river, a crag or hill begins to force roads out of symmetry and the logical array of street names submits to the sirens of chaos.

Emotional events, too, can induce the populace to change names as happened in Cincinnati, Ohio during World War I when German Street became English Street, and Hapsburg became Merrimac, along with other Anglicizing revisions. Deaths and assassinations of heroes can also cause a rash of street (as well as school) name changes, such as with the untimely losses of Earhart, Presley, and teacher/astronaut McAuliffe, and the murders of two Kennedys and a King. In other words, planned naming schemes just cannot stand up to the forces of love and hate either.

Even though some towns have adhered to their schemes quite meticulously, they still end up with a potpourri of street labels because their naming gimmick is limited or just plain inadequate. For example, using letters of the alphabet gets you 26 designations, not much for a growing municipality. Using presidents' names gets you a few more. Tree types, a classic theme, might yield a few dozen unless you get quite specific with names like Shag Bark Hickory Street and Horse Chestnut Circle. been sprouting up across the country since the end of the Second World War. Developers of these communities, knowing that quaint sells, have adopted themes honoring medieval England, flowers, nursery-rhymes, Indian artifacts, old cars, race horses and all sorts of other things. When William Levitt built one of the first communities on the Island Trees farm on Long Island in 1947, he divided it up into sections each with a theme for its streets. In the bird section, for example, there was Kingfisher Road, Grouse Lane, Magpie Land, and so on. In the cosmology section there was Polaris Drive, Horizon Lane and other astral names.

My own family used to live in a development called Gettysburg Estates with its Harper's Way, Shiloh, Meade, Pickett's Way and other streets labeled with apt Civil War references. Quaint? Picturesque? Makes you wonder if the developer wanted homeowners to envision ricocheting bullets and cannon ball craters, or to hear the ghostly agony of dieing soldiers from their porches, or to imagine mowing around the bodies and tombstones.

In San Lorenzo, California, the street naming motif is influenced by the Spanish in its past, thereby lending the mystique and beauty that so often accompanies ignorance. Its street signs displaying Via Del Sol, Via Encinas and Via Del Prado would delight even a tract developer on the outskirts of Cleveland. Who would care that Via Pecora means "Street of the Head of a Sheep," or Via Milos means "Street of the Earthworm," and Via Melina means nothing at all.

Such motifs may seem silly or superficial but it is all a necessary game. You have to designate the byways somehow so why not have some fun with it. On the other hand, some developers have gone to the lazy extreme with some particular theme when they use the same word in every street name in the community. In Waterford Meadows, west of Pontiac, Michigan, you can live on Meadowgreene, Meadowcrest, Meadowdale, Meadowoods or other such larks including Meadowlark. I suppose they get a lot of mail mix-ups there; some by postal accidents, some by postal revenge.

But you have to admit that when it comes to small community developments, name motifs for the roads seem kind of neat and practical. What is your favorite topic? Maybe it is the great classics of literature. You could give the roads such grand names as Iliad Lane, and Das Kapital Court or Main Street Street. How about movie stars, or old cars? If I had the chance to create a community, I would call it Vegetable Gardens with streets like Cucumber Court, Asparagus Avenue, Broccoli Lane, and Carrot Drive. Or how about a theme of generic road designations? We could have Avenue Way, Circle Square, Boulevard Lane, and Cul de Sac Court.

Very often the street names are created from fluff words, like View, Grand, Crest, and Green. Such words are versatile and ubiquitous because they are uncontroversial and inoffensive. There may not be a street named Glencrest anywhere in the country but you would swear there was because it sounds like Glenview and Hillcrest, both of which are popular street names. Like elevator music or cotton candy, these fluff names lack character and spirit but they also are not haughty and overbearing. They are ordinary, therefore not bad. They are sufficient if not stimulating. And they are, after all, no less meaningful than the names of the dead and forgotten.

Hollywood and Vine [touch]

The banality of such fluff names is illustrated by the Street Name Generator. Click the button and get a bucolic name. Or simply take one word from each of the three columns given there and you get a street designation as distinctive as a cud chewing cow in a grazing herd. Of course, we could add many more pleasant sounding words to the table, enough so that the road network of the entire country could be relabeled.

Imagine Saks Fifth Avenue having to rename itself Saks Fawn Creek Chase. Or how about that famous crossroads "Hollywood and Vine" becoming "Sunny View Glen and Green Haven Run?" (See picture at right.) After awhile, the melodic quality of these compound fluff names gets to sound like a Gregorian chant. Now there is an idea! Kyrie Eleison Way, Spiritu Santo Drive, Gloria in Excelsis Circle or Sanctus Dominus Lane.

Off the wall names may sound silly, but they are generally more easily remembered than a triplet of fluff names. Try it. Use any random object you think of as the basis for a name. How about Cotton Ball Way? Such a creative naming scheme can produce quaint and picturesque labels, like Lag Bolt Lane, Butter Dish Drive, Shoe Lace Run or Nails Clipper Crest.

In Maryland, in the relatively new town of Columbia, they used this approach and came up with such street names as Each Leaf Court, Smokey Wreath Way, Fruit Gift Place and Lambskin Lane. They should rename the town to something like Clever Name City. But even here a whole town of such colorful names begins to sound just as much like a church litany as the triplets of our street name generator. "Does he live on Round Peg Way or Square Hole Lane?" In such a town, the people on Second Street would be ones with the unforgettable addresses.

Advertisement

If urban and suburban roads are like rabbits – multiplying and consuming the farm – then interurban roads are like snakes, lonely wigglers darting around the countryside, racing through cities, rarely answering to a name. If you were to ask an interstate highway its name, it might say something like, "I Ninety Six."

It all began when the Romans brought engineering excellence to the barbarians and the improved byways came to be known as "high streets." Although these roads were often higher than the surrounding country and crown-shaped so that water would roll off, the reference more likely comes from the secondary definition of "high" to mean important, so that a "high" way was a main thoroughfare. The most popular street name in medieval southern England was High Street. In the north, the old Norse word for street, "gata," gave rise to High Gate. Over the ages, these main thoroughfares became turnpikes, motorways, expressways, freeways, and even skyways – but most often just highways.

Highway names, unlike street names, were hardly ever a big concern to anyone. They were generally called by one of their end points, like the Oregon Trail, or some salient feature, such as the Old Forest Road or Stone Road. In colonial times access to the hinder land was by means of Indian trails and these often had several names. Only through incidental consensus did the European settlers in the area eventually choose one name that became official.

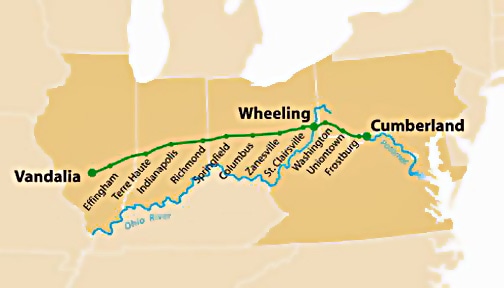

The first planned highway in the United States was the National Road begun in 1810 to move the people and goods across the vast new nation. This macadamized road, nearly seventy feet wide, was to be a major route into what was then called the Northwest, later called the Midwest, and now actually the Mideast. Originating in Maryland and snaking west across steep Appalachian country, the National Road reached Wheeling in 1818 where travelers had to cross the Ohio River by ferry. From there the road made its way to Columbus, Ohio, then as straight as an arrow shot to Indianapolis and beyond. The National Road has since been cannibalized by newer routes, including one designated as U.S. 40, not exactly a warm tribute to the historically significant byway.

Another notable and historic American road was one called the Lincoln Highway. It began when Carl Fisher, a flamboyant Hoosier who made millions selling gas headlamps for cars, led a caravan called the Trail Blazers from Indianapolis to Los Angeles in 34 days. The tortuous journey made news and by the end of the year the whole nation was celebrating the idea of a transcontinental road linking New York City and San Francisco. It took a decade to finish, but soon lost its prominence in a nation gone crazy with cars and roads. Now the Lincoln Highway lies old and broken, straggling slowly in and out of quaint towns, wearing historical markers like war ribbons.

Then in the 1920s, when American interurban roads began to flourish, the U. S. government decided to establish a numbering scheme for interstate highways. The roads were to be numbered consecutively north to south with odd numbers and east to west with even numbers. Thus, the now famous U. S. 1 traveled along the east coast from the Maine-Canada border to the tip of Florida.

A few of the roads also carried some heartfelt memorial designation the origin of which is inevitably lost to obscurity, or they may have had some informal name, such as Old Plank Road or Indian Trail. But by and large, official maps showed the ordinal designations.

Given the tradition of numbering the national highways in America, it was only natural that when President Dwight David Eisenhower proposed a postwar interstate system of roads in the U.S. a new numeric scheme was adopted. This time, however, it would be utterly systematic, pure governmental utilitarianism, functional to a fault. It would be as logical as it would be sterile, as purposeful as it was meaningless.

The scheme was simple. Two digit numbers would be assigned to approved interstate arteries. East-west roads would be given even numbers beginning from the south. North-south roads would be given odd numbers beginning in the west. Oh, by the way, sometimes there are spurs or shunts through or around major cities; each of these is given a three number designation by adding a significant digit of no particular significance.

Now, it is only natural that anomalies should arise in this rational system because rational systems are unnatural. For example, both I-81 in the Appalachians of the Virginia panhandle and I-85 at Charlotte, North Carolina cut westward across I-77 even though their designations could have been swapped at the intersection to preserve the order. Between Atlanta and Montgomery I-85 should be I-18. And I-69 just outside of Dewitt, Michigan becomes an east-west road on its way to Port Huron.

Then there is I-90 which goes west from Boston. In Elyria, Ohio, it joins up with I-80 from New York and they share the pavement to Gary, Indiana. There they split up and I-80 takes a new partner, I-94. But that union lasts only a little while and I-80 heads for San Francisco by itself. Meanwhile, I-90 joins up with I-94 again in Chicago only to separate a bit later. In Madison, they wed again, separate again upstate, then join up once more in Billings where I-94 dies and I-90 goes to Seattle alone. They should rename I-90 to I-Elizabeth Taylor,, eh?

That is not such an outlandish idea. Hundreds of stretches of the interstate system have already been renamed, like the Gene Autry Memorial Interchange (I-5) in California, the Dan Ryan (I-90 – I-94) in Chicago, and the Gerald R. Ford (I-96) in Grand Rapids. And it does not have to be a person. There is Century (I-105) in California, Black Canyon Freeway (I-17) in Phoenix, and Anacostia Freeway (I-295) in D. C. Even that old romantic numbered highway, Route 66, is known variously in towns it crosses as Alosta, Foothills Blvd., Colorado Blvd., Main St., Broadway, Fair Oaks, and Sunset Blvd.

There are dozens of Veterans Memorial Highways. And there are at least six Pearl Harbor Memorial Highways, most notably Interstate 10 in the Grand Canyon State. The Pearl Harbor Memorial Highway in Arizona seems a courteous reply to the Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii – like saying "you're welcome" to "thank you."

What is a better system you ask for designating over 46,000 miles of interstate concrete and asphalt? The highway planners might have begun with a three or four digit scheme to encode more information in the labels, or they could have embedded State references like 69MI, or they could have even used end point designations, like LA-DC. Or how about naming all the north-south interstate roads after past presidents, the east-west roads after the deceased chief justices? If we run out of names, no new highways until somebody dies.

I have an even better idea. The federal government could generate significant revenues by auctioning off the naming rights for segments of the national highway system. Imagine getting the Google Maps directions to Idaho: Take Interstate McDonalds to I-IBM, then head south until you get to I-Amway in Iowa. Next take I-"I Can't Believe It's Not Butter," and then head west to the intersection of I- Johnson & Johnson and I-Abercrombie & Fitch.

Well, maybe that is not such a good idea.

[ -- Go to top of page -- ]